This post may contain affiliate links. See my disclosure policy.

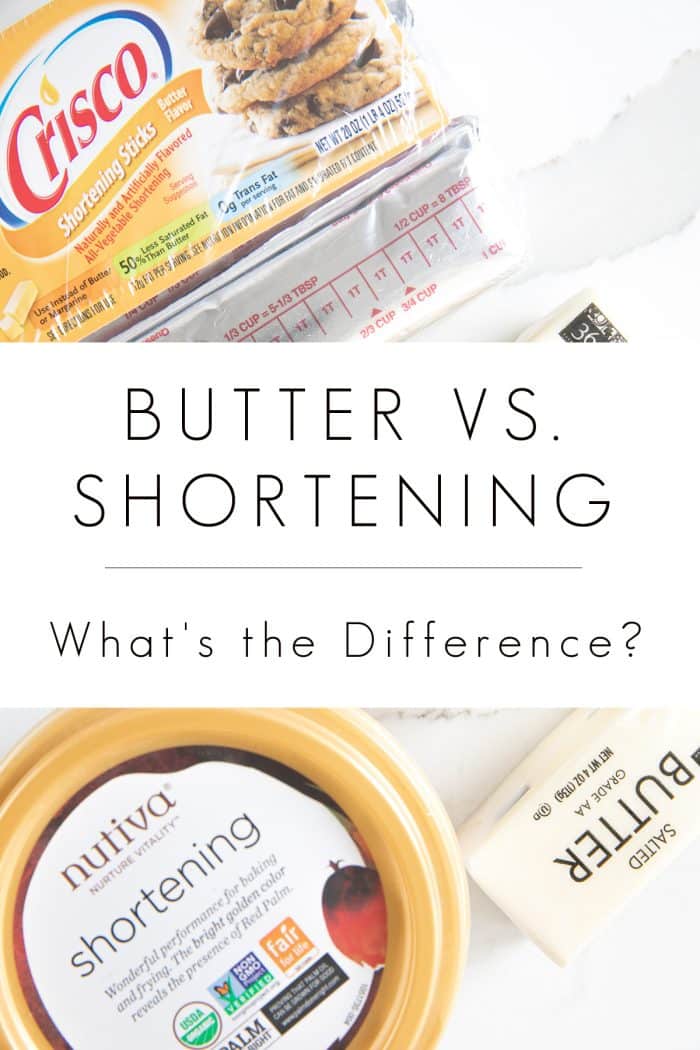

Have you ever wondered about the difference between butter and shortening and when to use each one? Today we’re exploring shortening vs. butter and the differences that make them so great.

We focus so much on proteins and starches, but often forget about fats? Cooking fats make things taste better, aid in the cooking process, and are a necessary part of our diet. So which type of fat should you use?

You may have read our post on Ghee vs. Butter, where we explored the pros and cons of those two great ingredients. Butter’s next competitor is shortening, a classic inclusion in the most indulgent baked goods.

In this post, I’ll show you the main differences between these two fats, the best way to use each one, and recipe options that highlight their greatest attributes.

Definitions

What is butter?

Butter is a dairy product made from the fatty cream of cow’s milk, called buttercream.

Butter is 80% fat, contains 16% moisture, and 2% milk solids. At room temperature, it is a semi-solid emulsion, but can be melted according to our needs.

Small-batch butter is made by heavily churning (agitating and mixing) cream to the point where butterfat separates from the water-based portion of the cream.

Nowadays, butter production is fully industrialized. In large facilities, buttercream is separated from the rest of the raw cow’s milk in a massive spinner, the cream is siphoned off and churned, and any extra moisture is removed during the process.

What is shortening?

Shortening, on the other hand, is any cooking fat made from partially hydrogenated vegetable oil.

Hydrogenation occurs when liquid vegetable oil is made solid by bombarding it with hydrogen atoms, raising the smoke point and stability.

This process changes the chemical structure of the oil from mostly unsaturated to saturated fats, leading to different uses in the kitchen.

Shortening is 100% fat and has little to no moisture content. It also has a fluffy texture, which makes it great for different types of baking and cooking.

History

How did shortening come about?

It was initially created by Procter & Gamble in the early 1900s to be a cheaper alternative to animal lard and tallow.

More shelf-stable and less expensive than butter, it became a staple in American households during uncertain times.

Shortening was developed specifically for baking.

It got its name from the way it “shortens” gluten chains. Instead of liquid oil that blends into the flour, this solid fat melts over time into the mixture, creating space that disrupts the gluten.

Consider the difference between a loaf of bread and a scone. Loaves of bread are made from stretchy glutens and have a spongy crumb.

Shortening reduces the length of the gluten strands and prevents the flour from absorbing water, which makes for crunchy, layered pastries. Baking is still the primary use for this ingredient.

Butter, on the other hand, has a far richer history.

It has been produced by almost every world culture for centuries. It first came about during the early domestication of herding animals, nearly 10,000 years ago.

NPR that a 4,500-year-old limestone tablet exists illustrating how butter was initially made, and the technique hasn’t changed much since!

Traditionally produced in small batches, Scientific American tells us how ancient cultures made animal skin bags to spin raw milk or cream to make butter.

History suggests that butter was probably first created by accident as a result of transporting and thereby churning cream. It was then incorporated into the daily diet as a way to store valuable dairy through the seasons and help prepare proteins.

Recipes and Usage

Now that we know a bit more about our favorite fats, what can you do in the kitchen with butter and shortening?

Butter:

- Sauteing: Butter has high moisture levels and therefore is not suitable for high-temp frying. However, the moisture is great for sauteing and infusing sauteed foods with all that buttery flavor. It’s the perfect pick for making easy fried rice at home.

- Flavoring: There is no shame in coating foods in butter for that creamy, rich flavor. I use butter to fry up lean pork chops. Roasted vegetables aren’t the same without being drenched in butter, then seasoned. Try out this roasted asparagus as a perfect buttery and crunchy side dish to any main!

- Baking: Butter is incredibly versatile when baking. Many breads, pastries, and cookies would not be the same without it. Traditionally, pie crusts and biscuits were all made with cold butter to infuse that signature flavor while creating a flaky texture.

Shortening:

- Frying: Shortening is great for frying due to its high smoke point.

- Frostings: We need creamy frosting as a blank canvas in cake decorating. Wiltons, the renowned icing brand, claims that shortening is the best option for creating beautiful frostings for all decorative use.

- Baking: Shortening is a popular choice when baking decadent pastries and certain types of cookies. It can be used instead of butter in pie crusts, and lots of southerners use it alongside butter to top their biscuits.

Cold butter is used similarly to shortening when making biscuits or croissants. It is placed evenly into the dough while ice cold and not allowed to melt before baking. Therefore, it melts when in the oven, disrupting those gluten chains and making buttery, flakey goodness within.

I use butter to create fluffy, cakey dumplings in one of my favorite southern-inspired dishes, chicken and dumplings. This recipe is an excellent example of mixing butter with flour to create that biscuit-like effect. However, some people use only shortening in their dumplings.

While butter is generally preferred by home cooks today, shortening is used in most industrialized settings. It is shelf-stable, cheaper than butter, and way less temperamental.

Shortening is better than butter for frying, as it has a higher melt point and is more heat-stable. Foods cooked in shortening are also considered less greasy – a traditional method for making southern fried chicken uses shortening rather than oil.

Nutrition

Some say butter is not the healthiest choice when cooking, but compared to shortening, it packs way more nutrition value.

Harvard Public Health even states that fats are crucial to our health, and butter is more of a natural and heart-healthy ingredient overall.

Shortening should not replace more beneficial fats and oils whenever possible. It is perfect for frying, but not any better than refined vegetable oil as far as health benefits go.

When it comes to cooking tasty and healthy food, I tend to reach for butter (or olive oil).

Let’s take a look at some basic nutritional data and see how each of these fats stack up.

Per (1) Cup of Butter:

- 1628 Calories

- 184 grams of Fat

- 117 grams of Saturated fat

- 1.9 grams of Protein

- 0.1 grams of Carbohydrates

- 0 grams of Fiber

- 0.1 grams of Sugar

- 1460, milligrams of Sodium

Per (1) cup of shortening:

- 1840 Calories

- 208 grams of Fat

- 83.2 grams of Saturated Fat

- 0 grams of Protein

- 0 grams of Carbohydrates

- 0 grams of Fiber

- 0 grams of Sugar

- 0 milligrams of Sodium

At first glance, butter doesn’t look much healthier than shortening. But I assure you, butter has a stronger nutrient profile and is more naturally digested by our bodies.

It’s also lower in fat, and it has more healthy components like vitamins and minerals. Not to mention its robust, umami, almost nutty flavor and creamy texture – even when melted.

Shortening is essentially free of character in terms of taste. It is a neutral fat that is void of any nutritional value and relies only on its physical and heating attributes for merit.

Terms to Know

There are so many different types of fats, shortenings, and kinds of butter on the market these days.

Keeping these terms in mind will help you navigate the grocery store and your recipe books to know exactly which type of fat fits your needs.

- Salted butter: Basic sea salt has been added to the butter to enhance flavor.

- Unsalted butter: Simply means no added salt, though butter does have natural salt.

- Clarified Butter: Milk fat is rendered to remove the solids and moisture from butter. This intensifies the flavor slightly and gives the butter a higher smoke point.

- Plant-based butter: Dairy and gluten-free butter made with a mixture of plant-based oils. The higher quality plant butters are made with coconut, olive, avocado, and almond oils.

- Margarine: A spreadable butter-like product made with refined, low-grade, vegetable oils, and water. It is usually made to mimic the natural flavor of butter.

- Lard: Made by rendering the fatty tissue of swine. It is semi-solid and traditionally used as a shortening, though it has been replaced by vegetable shortening in most recipes. The fat leftover from baking bacon in the oven can be rendered into homemade lard that has countless cooking applications.

- Shortening: Anything used to shorten gluten molecules in baked goods.

- All-purpose Shortening: The gooey stuff in the jar, made of hydrogenated vegetable oil. Specially texturized to be used in baking, it has a wide range of bakery applications.

- Icing Shortening: Emulsified with water and specifically formulated to blend with higher ratios of moisture and sugar for icings that won’t melt at room temperature.

Having a few different fats to choose from in your pantry or fridge can open up many possibilities when it comes to cooking.

Experimenting with unfamiliar fats in various recipes will help to round out your skills and introduce you to new flavors and textures!

No two fats or oils are exactly the same, and each has its own set of pros and cons. Try out fresh takes on old favorites, challenge yourself with new ingredients, and enjoy everything the world of home cooking has to offer.

I think you meant “This process changes the chemical structure of the oil from mostly unsaturated to saturated fats…”. Hydrogenation “saturates” the lipid chain with hydrogen, causing it to become rigid.

Thanks for catching that typo 🙂

I have a hand me down recipe for cheese straws. The recipe calls for crisco. I was disappointed with my results. Eve. Though I used 1 pound of grated seriously sharp cheddar cheese there wasn’t the intense cheese flavor. The recipe called for 5 cups of all purpose flour which I felt could have been reduced. My question to you is regarding the amount of flour and certainly Crisco or butter.

Hi Rebecca,

It’s tough for me to say without seeing the recipe, and trying it myself to see the results as originally written. Only then could I take a go at tweaking a recipe that is not mine…